2008年5月翻译资格考试三级英语笔译实务真题及答案

VIP免费

3.0

2024-11-17

1

0

45.5KB

7 页

3.8金币

侵权投诉

2008 年 5 月翻译资格考试三级英语笔译实务真题及答案

试题部分:

Section 1: English-Chinese Translation (英译汉) Translate the following passage

into Chinese.

ARDEA, Italy — The previous growing season, this lush coastal field near Rome

was filled with rows of delicate durum wheat, used to make high-quality pasta.

Today it overflows with rapeseed, a tall, gnarled weedlike plant bursting with

coarse yellow flowers that has become a new manna for European farmers:

rapeseed can be turned into biofuel.

Motivated by generous subsidies to develop alternative energy sources — and a

measure of concern about the future of the planet — Europe’s farmers are

beginning to grow crops that can be turned into fuels meant to produce fewer

emissions than gas or oil. They are chasing their counterparts in the Americas

who have been raising crops for biofuel for more than five years.

“This is a much-needed boost to our economy, our farms,” said Marcello Pini,

50, a farmer, standing in front of the rapeseed he planted for the first time.

“Of course, we hope it helps the environment, too.”

In March, the European Commission, disappointed by the slow growth of the

biofuels industry, approved a directive that included a “binding target”

requiring member countries to use 10 percent biofuel for transport by 2020 —

the most ambitious and specific goal in the world.

Most European countries are far from achieving the target, and are introducing

incentives and subsidies to bolster production.

As a result, bioenergy crops have replaced food as the most profitable crop in

several European countries. In this part of Italy, for example, the government

guarantees the purchase of biofuel crops at 22 Euros for 100 kilograms, or

$13.42 for 100 pounds — nearly twice the 11 to 12 Euros for 100 kilograms of

wheat on the open market in 2006. Better still, farmers can plant biofuel crops

on “set aside” fields, land that Europe’s agriculture policy would otherwise

require be left fallow.

But an expert panel convened by the United Nations Food and Agriculture

Organization pointed out that the biofuels boom produces benefits as well as

trade-offs and risks — including higher and wildly fluctuating food prices. In

some markets, grain prices have nearly doubled.

“At a time when agricultural prices are low, in comes biofuel and improves the

lot of farmers and injects life into rural areas,” said Gustavo Best, an

expert at the Food and Agriculture Organization in Rome. “But as the scale

grows and the demand for biofuel crops seems to be infinite, we’re seeing some

negative effects and we need to hold up a yellow light.”

Josette Sheeran, the new head of the United Nations World Food program, which

fed nearly 90 million people in 2006, said that biofuels created new problems.

“An increase in grain prices impacts us because we are a major procurer of

grain for food,” she said. “So biofuels are both a challenge and an

opportunity.”

In Europe, the rapid conversion of fields that once grew wheat or barley to

biofuel crops like rapeseed is already leading to shortages of the ingredients

for making pasta and brewing beer, suppliers say. That could translate into

higher prices in supermarkets.

“New and increasing demand for bioenergy production has put high pressure on

the whole world grain market,” said Claudia Conti, a spokesman for Barilla,

one of the largest Italian pasta makers. “Not only German beer producers, but

Mexican tortilla makers have see the cost of their main raw material growing

quickly to historical highs.”

Some experts are more worried about the potential impact to low-income

consumers. In the developing world, the shift to more lucrative biofuel crops

destined for richer countries could create serious hunger and damage the

environment if wild land is converted to biofuel cultivation, the agriculture

panel concluded.

But officials at the European Commission say they are pursuing a measured

course that will prevent some of the price and supply problems seen in American

markets.

In a recent speech, Mariann Fischer Boel, the European agriculture and rural

development commissioner, said that the 10 percent target was “not a shot in

the dark,” but was carefully chosen to encourage a level of growth for the

biofuel industry that would not produce undue hardship for Europe’s poor.

She calculated that this approach would push up would raw material prices for

cereal by 3 percent to 6 percent by 2020, while prices for oilseed might rise 5

percent to 18 percent. But food prices on the shelves would barely change, she

said.

Yet even as the European program begins to harvest biofuels in greater volume,

homegrown production is still far short of what is needed to reach the 10

percent goal: Europe’s farmers produced an estimated 2.9 billion liters, or

768 million gallons, of biofuel in 2004, far shy of the 3.4 billion gallons

generated in the United States in the period. In 2005, biofuel accounted for

around 1 percent of Europe’s fuel, according to European statistics, with

almost all of that in Germany and Sweden. The biofuel share in Italy was 0.51

percent, and in Britain, 0.18 percent.

That could pose a threat to European markets as foreign producers like Brazil

or developing countries like Indonesia and Malaysia try to ship their biofuels

to markets where demand, subsidies and tax breaks are the greatest.

Ms. Fischer Boel recently acknowledged that Europe would have to import at

least a third of what it would need to reach its 10 percent biofuels target.

Politicians fear that could hamper development of a local industry, while

perversely generating tons of new emissions as “green” fuel is shipped

thousands of kilometers across the Atlantic, instead of coming from the farm

next door.

Such imports could make biofuel far less green in other ways as well — for

example if Southeast Asian rainforest is destroyed for cropland.

Brazil, a country with a perfect climate for sugar cane and vast amounts of

land, started with subsidies years ago to encourage the farming of sugarcane

for biofuels, partly to take up “excess capacity” in its flagging

agricultural sector.

The auto industry jumped in, too. In 2003, Brazilian automakers started

producing flex-fuel cars that could run on biofuels, including locally produced

ethanol. Today, 70 percent of new cars in the country are flex-fuel models, and

Brazil is one of the largest growers of cane for ethanol.

Analysts are unsure if the Brazilian achievement can be replicated in Europe —

or anywhere else. Sugar takes far less energy to convert to biofuel than almost

any product.

Yet after a series of alarming reports on climate change, the political urgency

to move faster is clearly growing.

With an armload of incentives, the Italian government hopes that 70,000

hectares, or 173,000 acres, of land will be planted with biofuel crops in 2007,

and 240,000 hectares in 2010, up from zero in 2006.

Mr. Pini, the farmer, has converted about 25 percent of his land, or 18

相关推荐

-

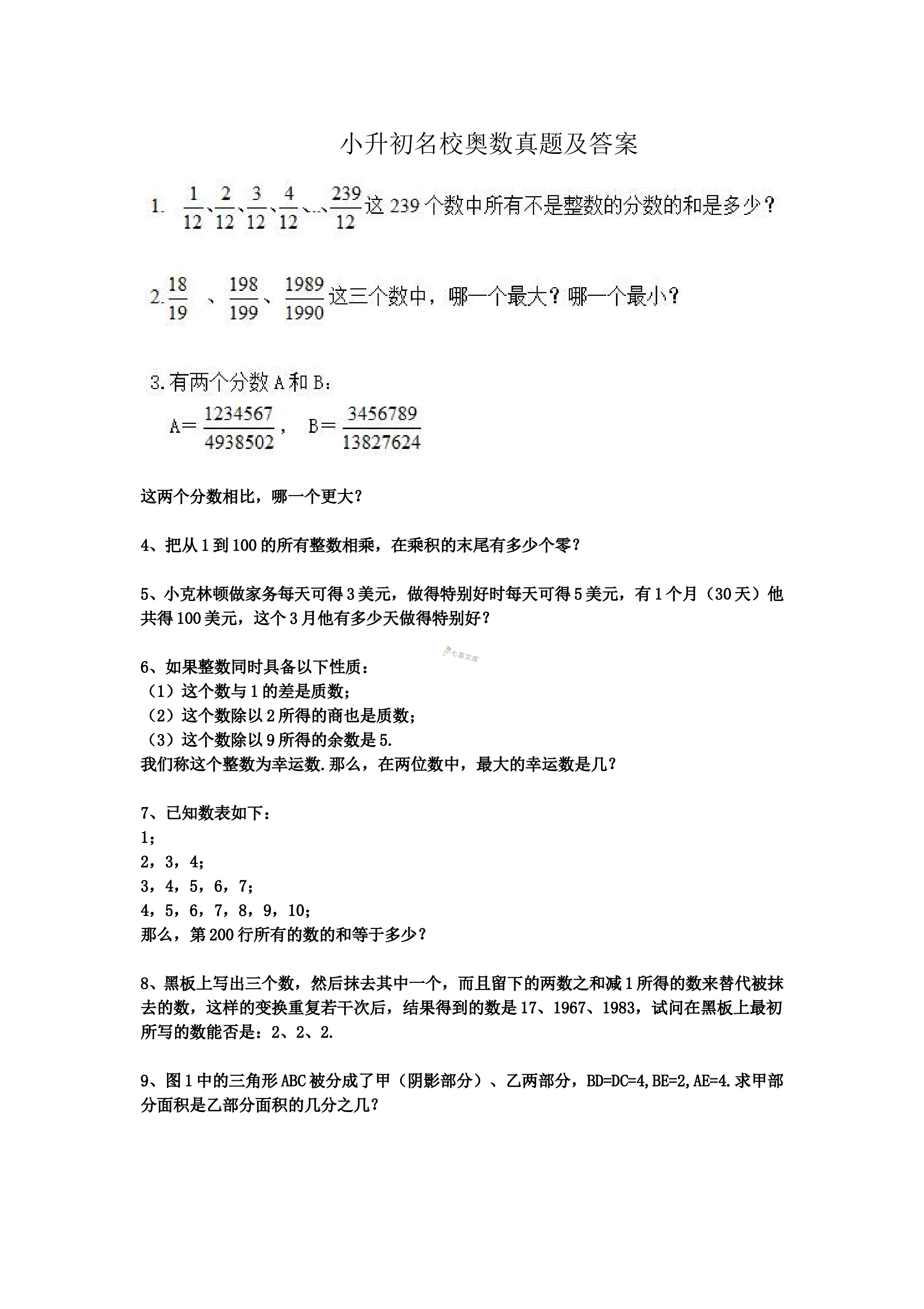

小升初名校奥数真题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-09 42

2024-11-09 42 -

2023-2024学年七年级下册数学第一章第七节试卷及答案北师大版VIP免费

2024-11-09 96

2024-11-09 96 -

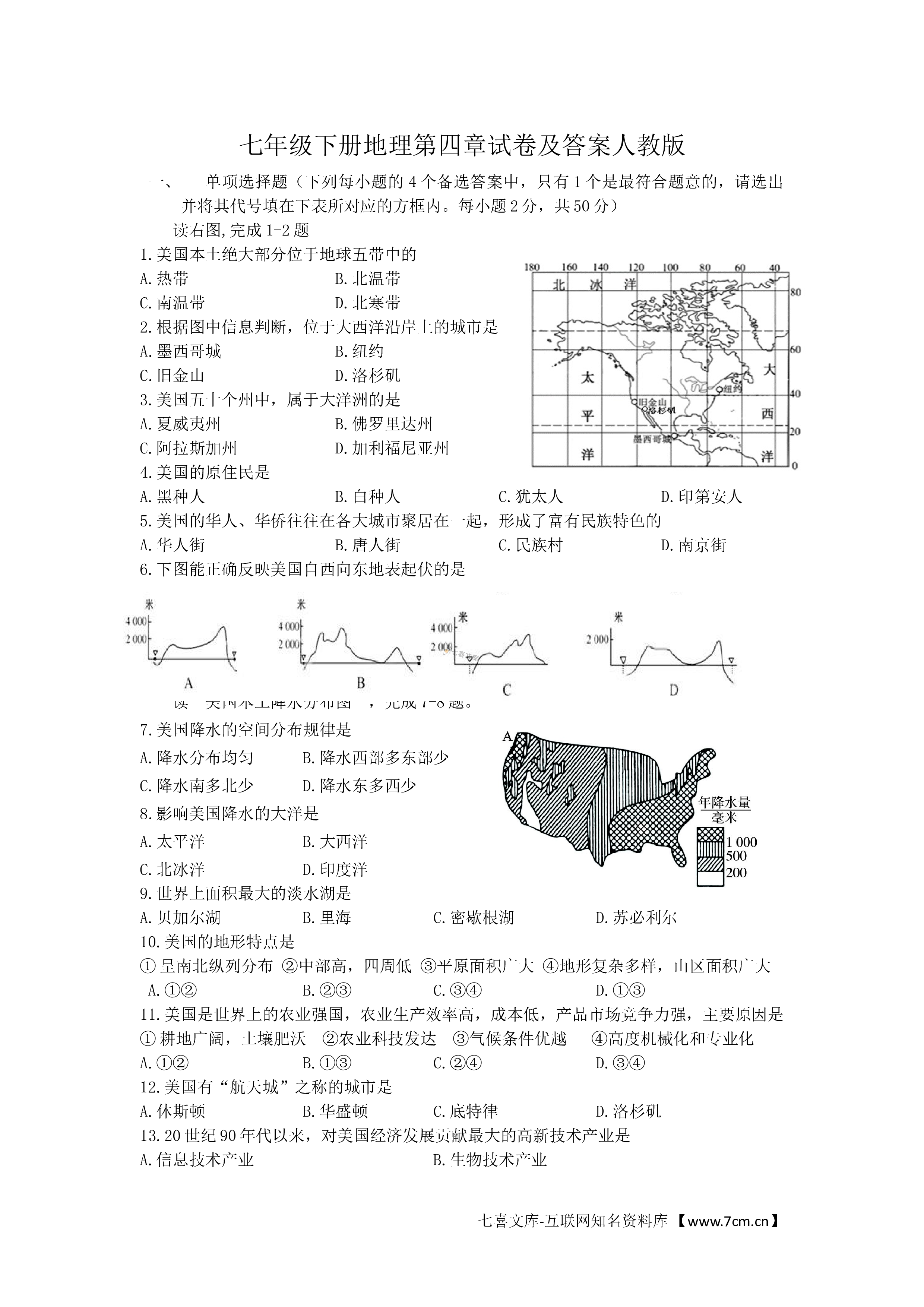

七年级下册地理第四章试卷及答案人教版VIP免费

2024-11-10 53

2024-11-10 53 -

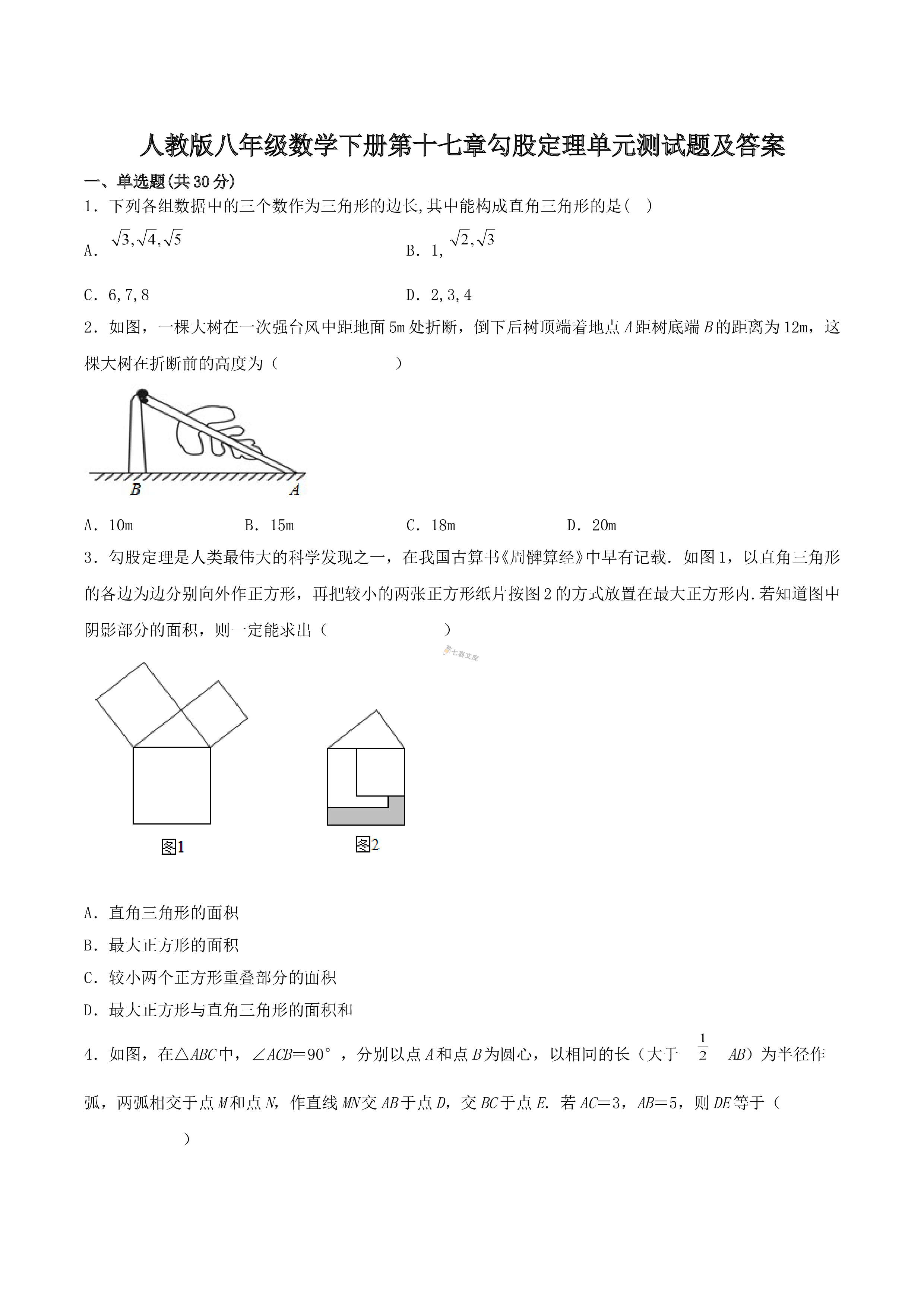

人教版八年级数学下册第十七章勾股定理单元测试题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-10 437

2024-11-10 437 -

2011年成人高考专升本生态学基础考试真题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-12 46

2024-11-12 46 -

2023年武汉工程大学教育管理学考研真题VIP免费

2024-11-14 18

2024-11-14 18 -

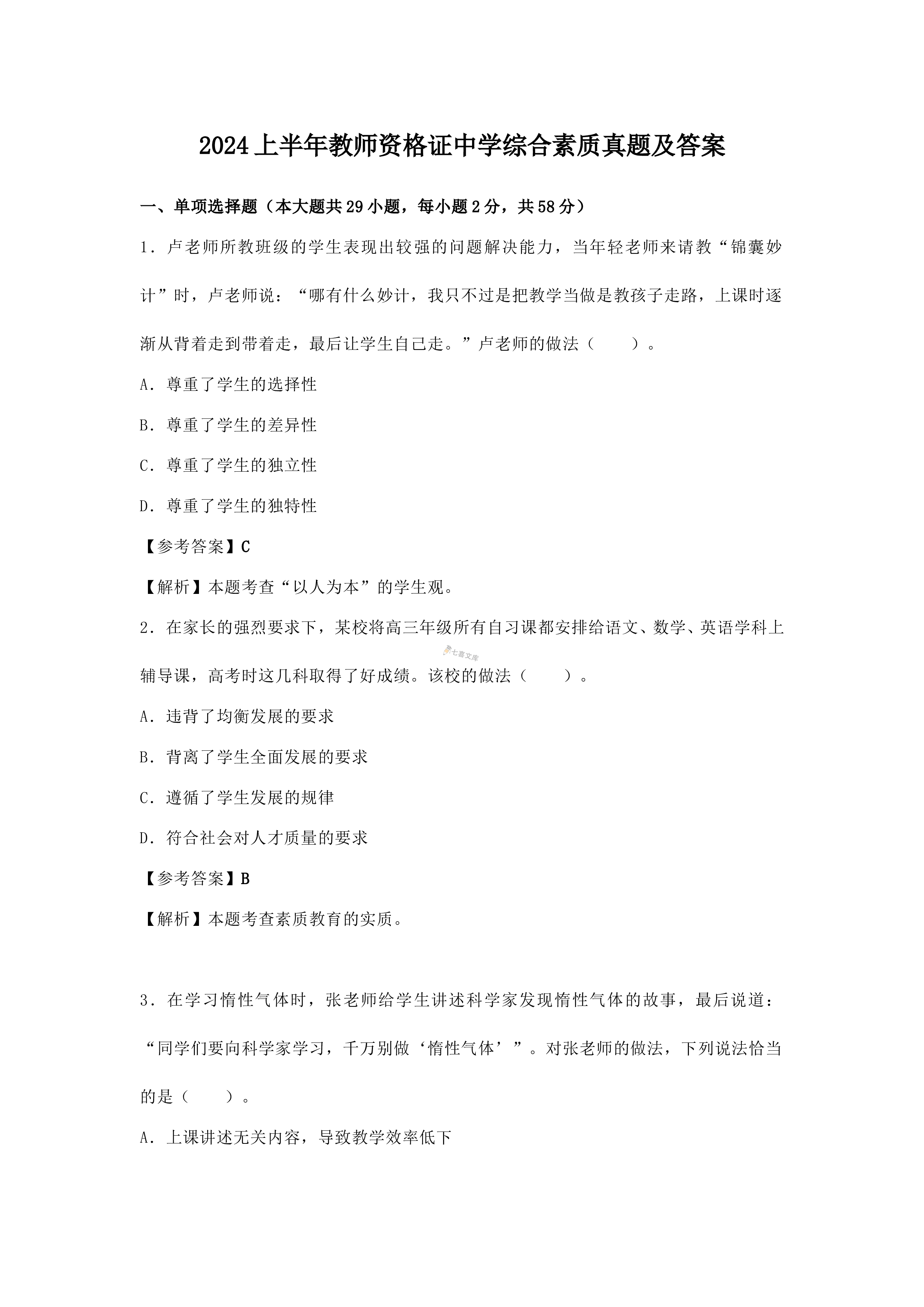

2024上半年教师资格证中学综合素质真题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-17 198

2024-11-17 198 -

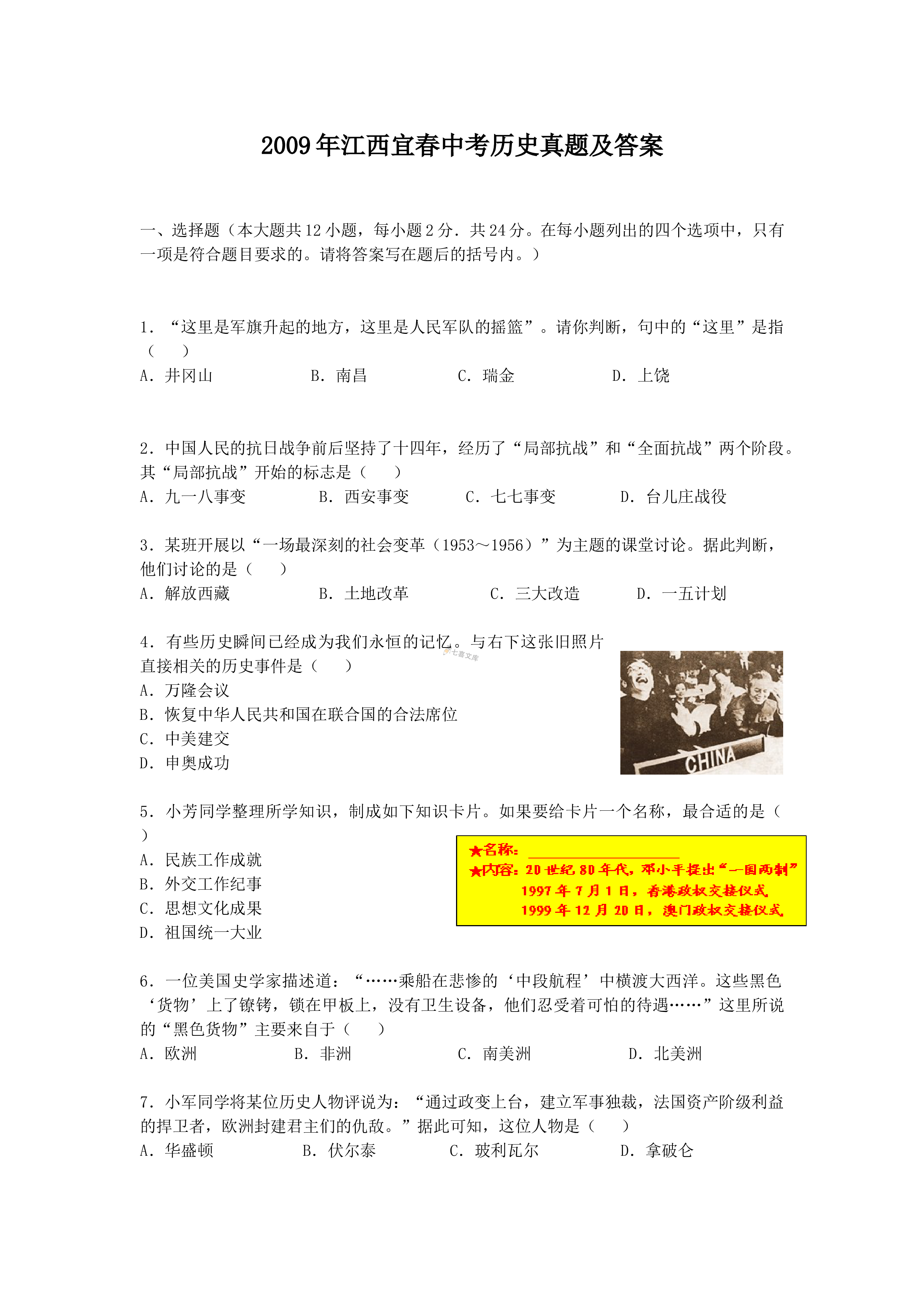

2009年江西宜春中考历史真题及答案

2024-12-24 13

2024-12-24 13 -

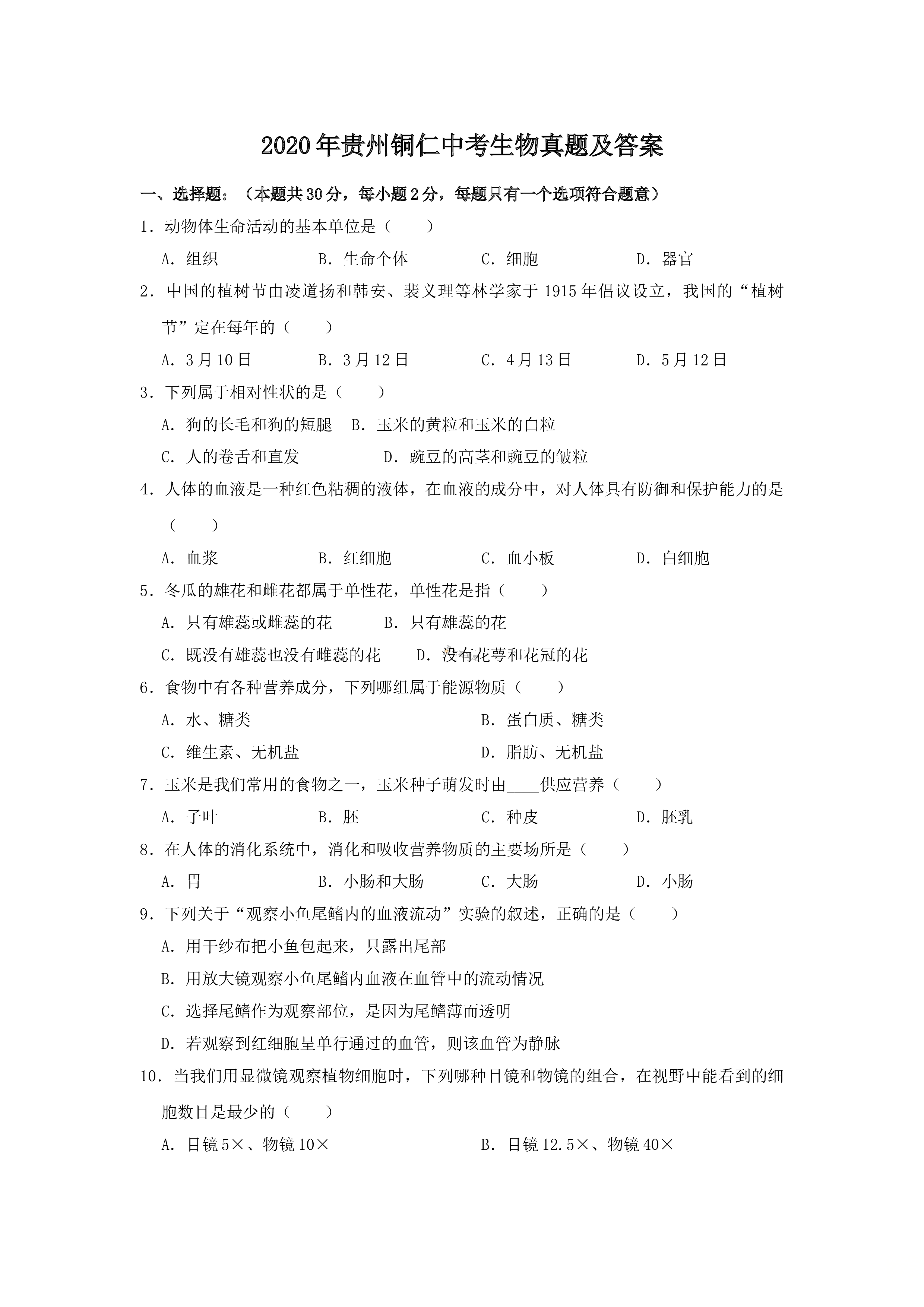

2020年贵州铜仁中考生物真题及答案

2025-01-04 14

2025-01-04 14 -

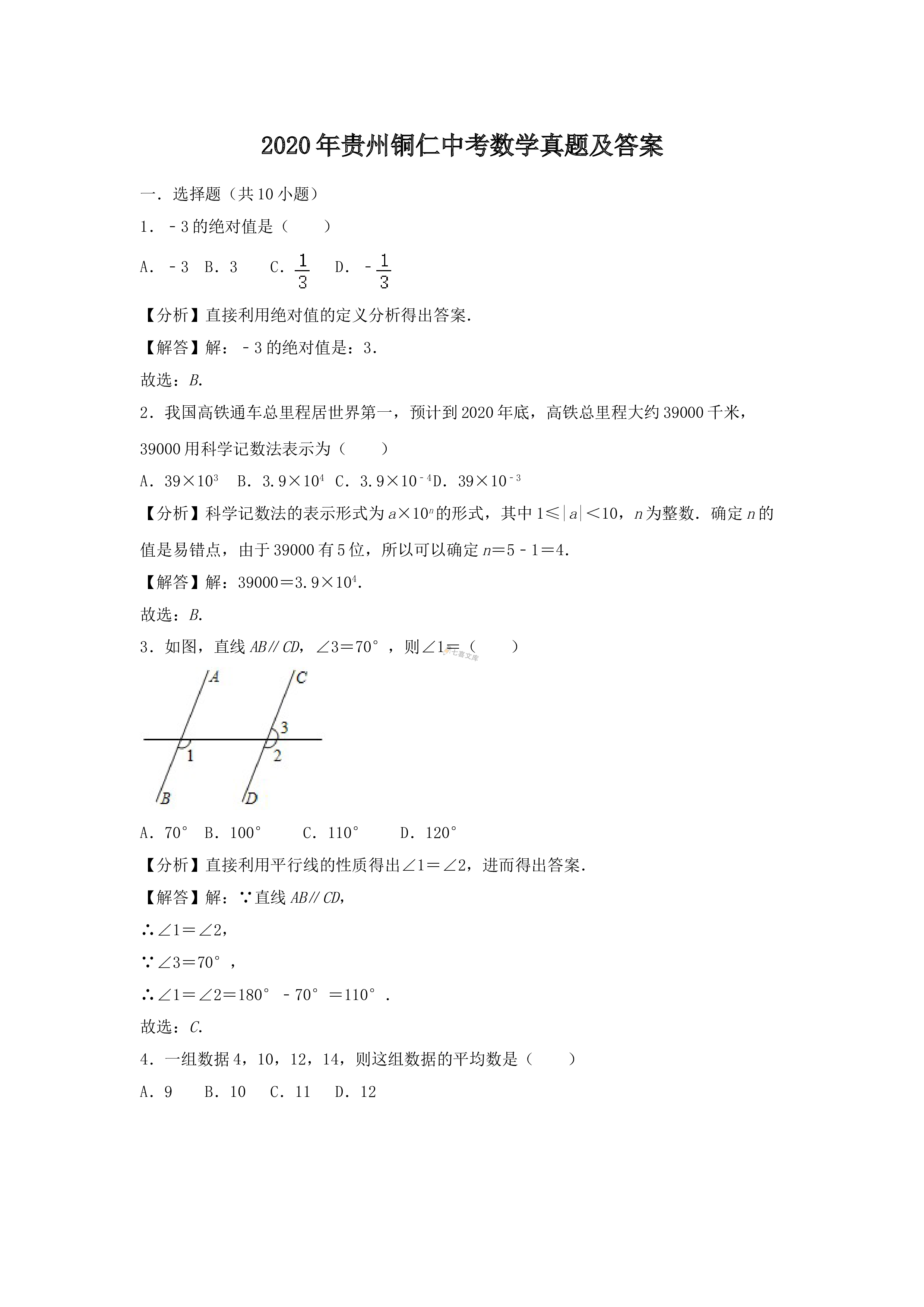

2020年贵州铜仁中考数学真题及答案

2025-01-04 16

2025-01-04 16

分类:行业题库

价格:3.8金币

属性:7 页

大小:45.5KB

格式:DOC

时间:2024-11-17

相关内容

-

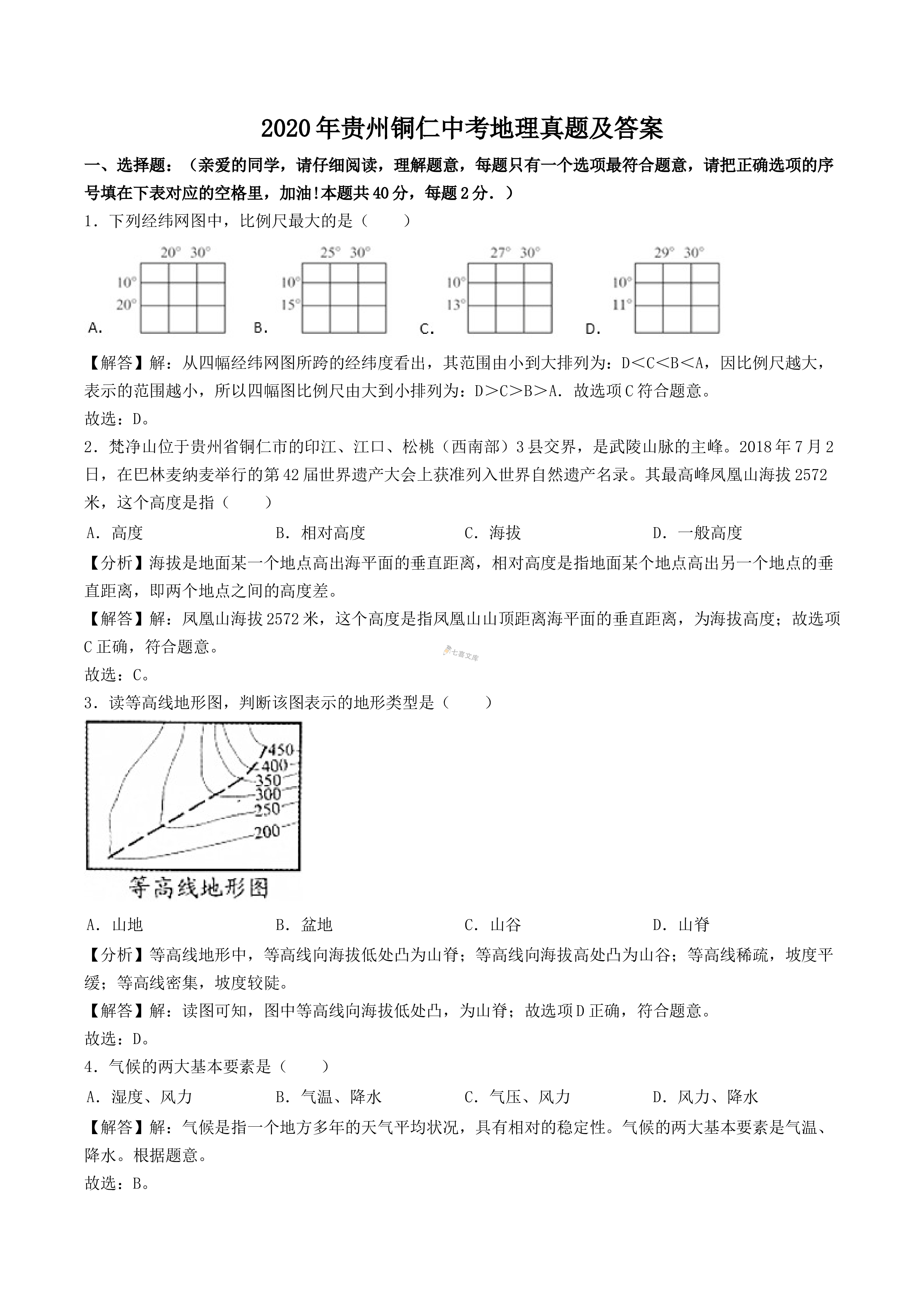

2020年贵州铜仁中考地理真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

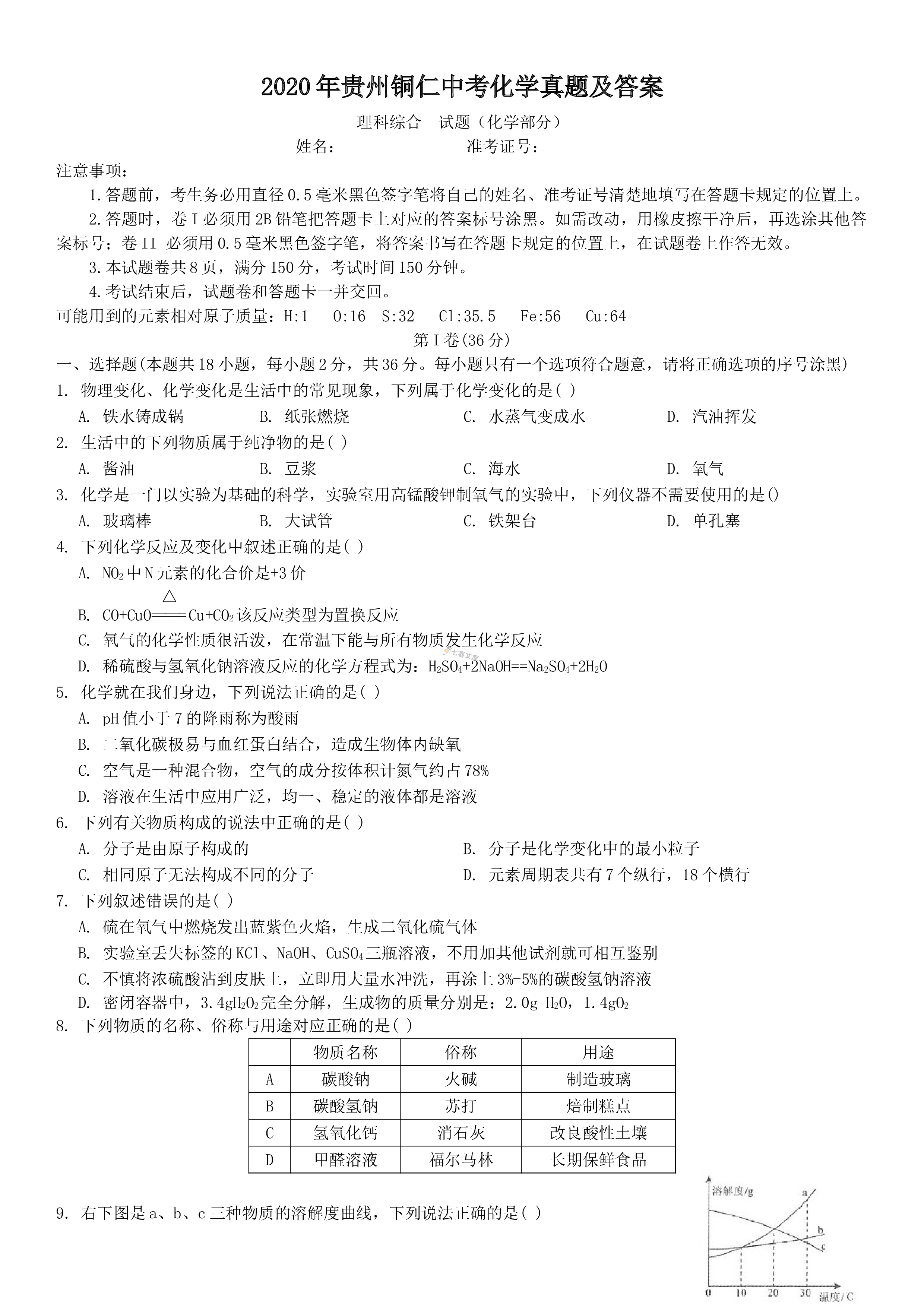

2020年贵州铜仁中考化学真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

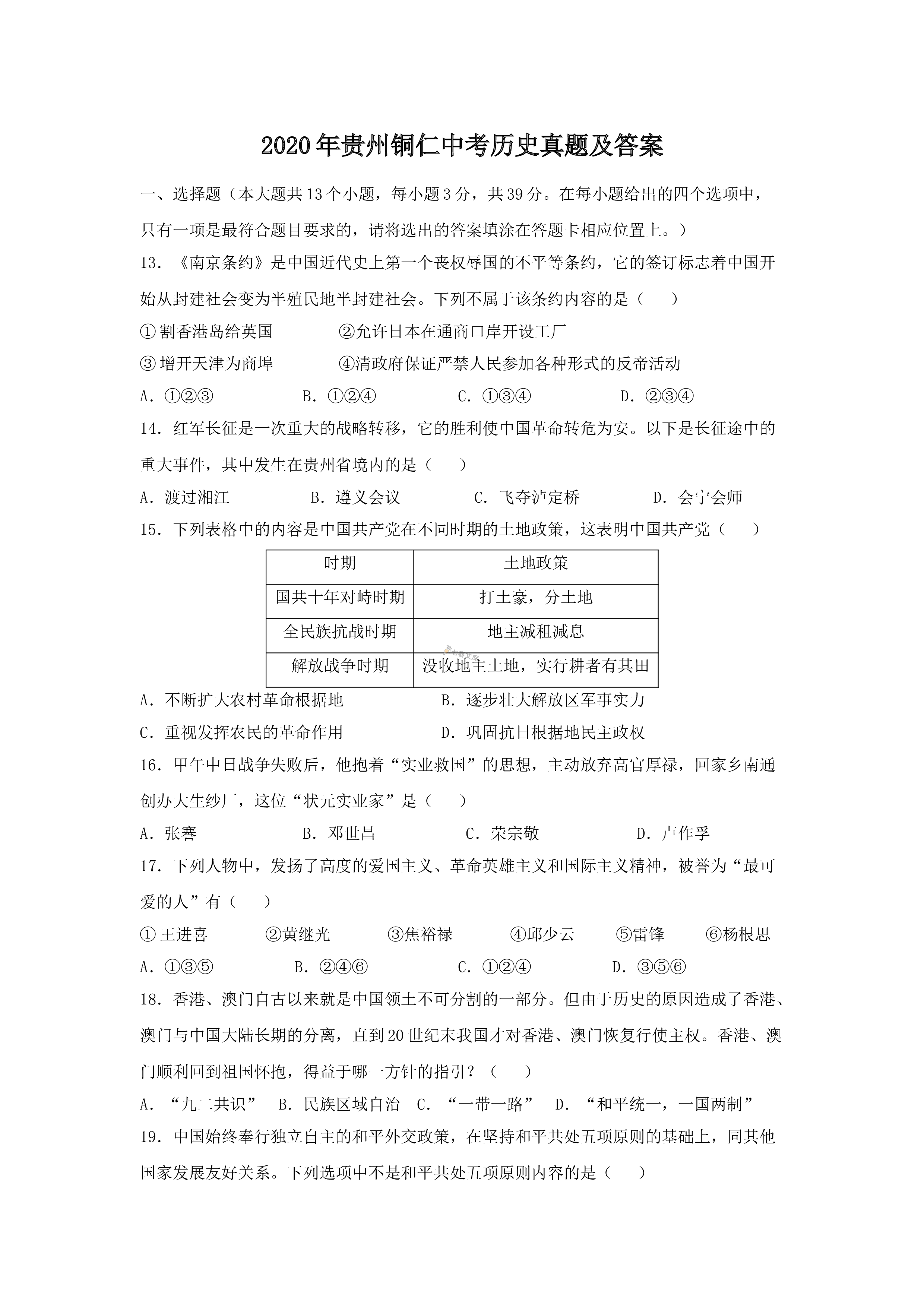

2020年贵州铜仁中考历史真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

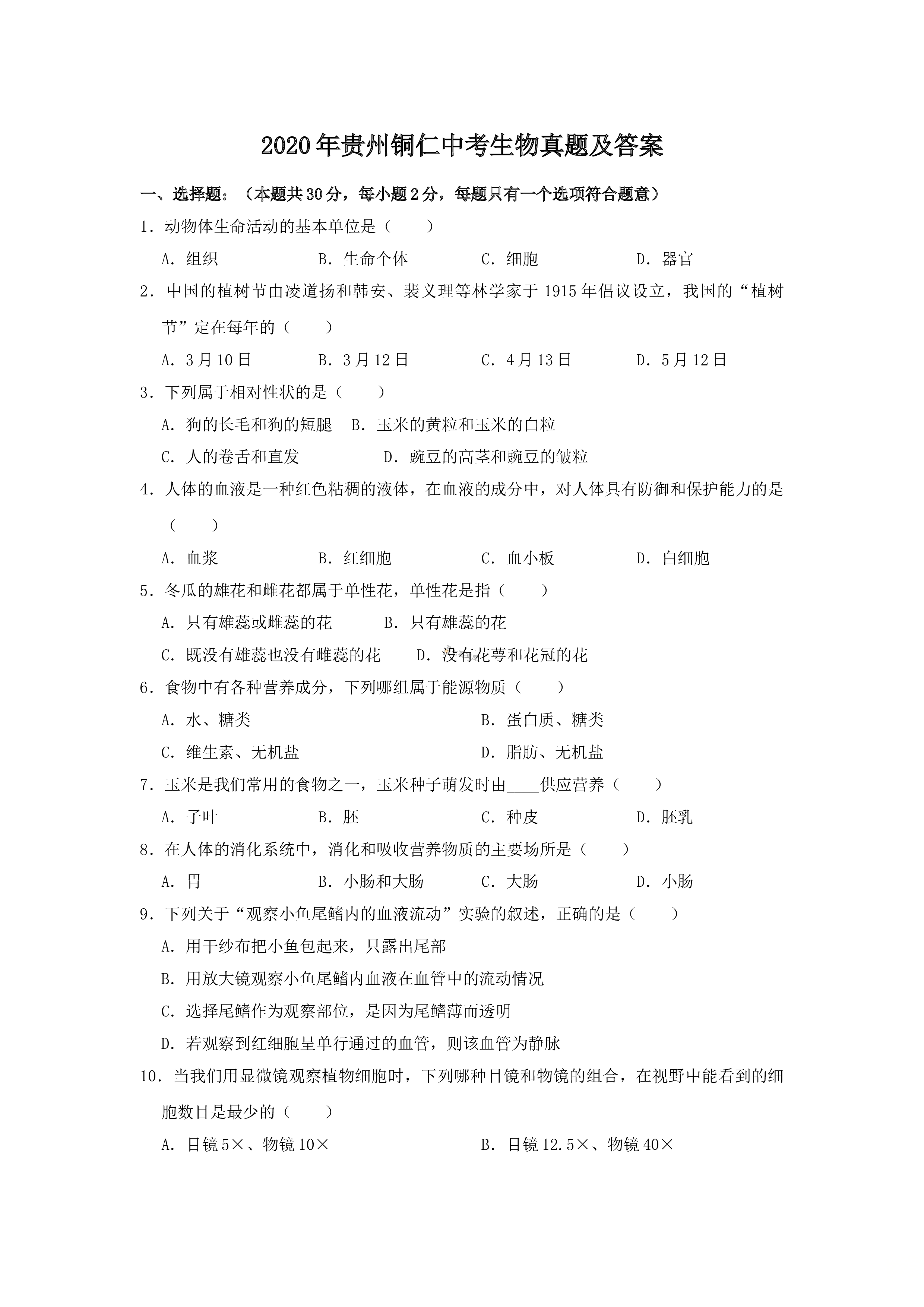

2020年贵州铜仁中考生物真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

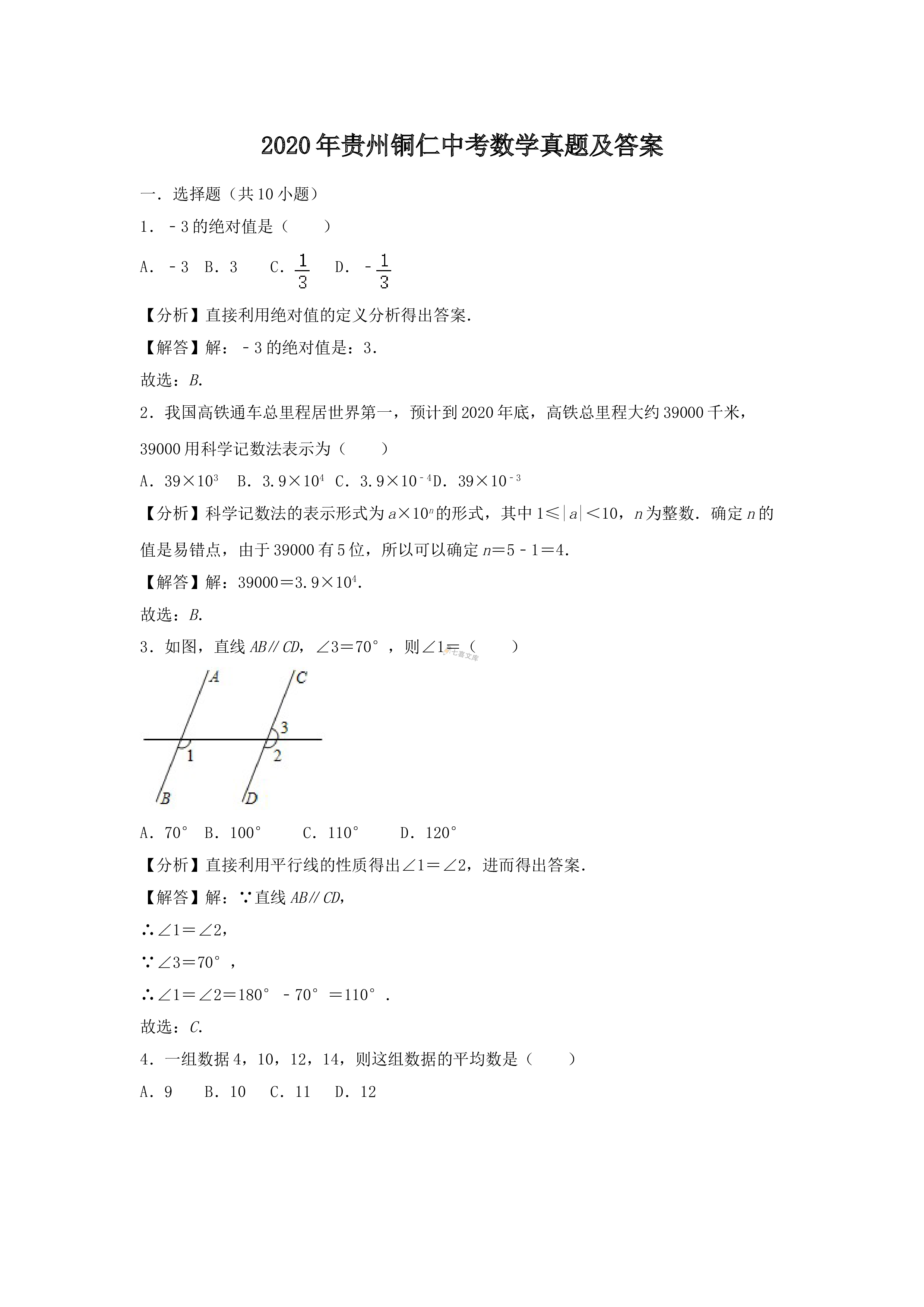

2020年贵州铜仁中考数学真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币