2012年12月英语六级真题及答案

VIP免费

3.0

2024-11-14

0

0

134.5KB

33 页

3.2金币

侵权投诉

2012 年 12 月英语六级真题及答案

Part I Writing (30

minutes)

Directions:For this part, you are allowed 30 minutes to write an essay entitled

Man and Computer by commenting on the saying, “The real danger is not that the

computer will begin to think like man, but that man will begin to think like

the computer.” You should write at least 150 words but no more than 200 words.

Man and Computer

Part II Reading Comprehension (Skimming and Scanning)(15 minutes)

Directions: In this part, you will have 15 minutes to go over the passage

quickly and answer the questions on Answer Sheet 1. For questions 1-7, choose

the best answer from the four choices marked A), B), C) and D). For questions

8-10, complete the sentences with the information given in the passage.

Thirst grows for living unplugged

More people are taking breaks from the connected life amid the stillness

and quiet of retreats like the Jesuit Center in Wernersville, Pennsylvania.

About a year ago, I flew to Singapore to join the writer Malcolm Gladwell,

the fashion designer Marc Ecko and the graphic designer Stefan Sagmeister in

addressing a group of advertising people on “Marketing to the Child of

Tomorrow.” Soon after I arrived, the chief executive of the agency that had

invited us took me aside. What he was most interested in, he began, was

stillness and quiet.

A few months later, I read an interview with the well-known cutting-edge

designer Philippe Starck.

What allowed him to remain so consistently ahead of the curve? “I never

read any magazines or watch TV,” he said, perhaps with a little exaggeration.

“Nor do I go to cocktail parties, dinners or anything like that.” He lived

outside conventional ideas, he implied, because “I live alone mostly, in the

middle of nowhere.”

Around the same time, I noticed that those who part with $2,285 a night to

stay in a cliff-top room at the Post Ranch Inn in Big Sur, California, pay

partly for the privilege of not having a TV in their rooms; the future of

travel, I’m reliably told, lies in “black-hole resorts,” which charge high

prices precisely because you can’t get online in their rooms.

Has it really come to this?

The more ways we have to connect, the more many of us seem desperate to

unplug. Internet rescue camps in South Korea and China try to save kids

addicted to the screen.

Writer friends of mine pay good money to get the Freedom software that

enables them to disable the very Internet connections that seemed so

emancipating not long ago. Even Intel experimented in 2007 with conferring four

uninterrupted hours of quiet time (no phone or e-mail) every Tuesday morning on

300 engineers and managers. Workers were not allowed to use the phone or send

e-mail, but simply had the chance to clear their heads and to hear themselves

think.

The average American spends at least eight and a half hours a day in front

of a screen, Nicholas Carr notes in his book

The Shallows

. The average American

teenager sends or receives 75 text messages a day, though one girl managed to

handle an average of 10,000 every 24 hours for a month.

Since luxury is a function of scarcity, the children of tomorrow will long

for nothing more than intervals of freedom from all the blinking machines,

streaming videos and scrolling headlines that leave them feeling empty and too

full all at once.

The urgency of slowing down—to find the time and space to think—is

nothing new, of course, and wiser souls have always reminded us that the more

attention we pay to the moment, the less time and energy we have to place it in

some larger context. “Distraction is the only thing that consoles us for our

miseries,” the French philosopher Blaise Pascal wrote in the 17th century,

“and yet it is itself the greatest of our miseries.” He also famously

remarked that all of man’s problems come from his inability to sit quietly in

a room alone.

When telegraphs and trains brought in the idea that convenience was more

important than content, Henry David Thoreau reminded us that “the man whose

horse

trots

(奔跑), a mile in a minute does not carry the most important

messages.”

Marshall McLuhan, who came closer than most to seeing what was coming,

warned, “When things come at you very fast, naturally you lose touch with

yourself.”

We have more and more ways to communicate, but less and less to say. Partly

because we are so busy communicating. And we are rushing to meet so many

deadlines that we hardly register that what we need most are lifelines.

So what to do? More and more people I know seem to be turning to yoga, or

meditation

(沉思), or

tai chi

(太极);these aren’t New Age

fads

(时尚的事物)

so much as ways to connect with what could be called the wisdom of old age. Two

friends of mine observe an “Internet

sabbath

(安息日)” every week, turning

off their online connections from Friday night to Monday morning. Other friends

take walks and “forget” their cellphones at home.

A series of tests in recent years has shown, Mr. Carr points out, that

after spending time in quiet rural settings, subjects “exhibit greater

attentiveness, stronger memory and generally improved cognition. Their brains

become both calmer and sharper.” More than that,

empathy

(同感,共鸣),as well

as deep thought, depends (as neuroscientists like Antonio Damasio have found)

on neural processes that are “inherently slow.”

I turn to eccentric measures to try to keep my mind sober and ensure that I

have time to do nothing at all (which is the only time when I can see what I

should be doing the rest of the time).I have yet to use a cellphone and I

have never Tweeted or entered Facebook. I try not to go online till my day’s

writing is finished, and I moved from Manhattan to rural Japan in part so I

could more easily survive for long stretches entirely on foot.

None of this is a matter of

asceticism

(苦行主义);it is just pure

selfishness. Nothing makes me feel better than being in one place, absorbed in

a book, a conversation, or music. It is actually something deeper than mere

happiness: it is joy, which the

monk

(僧侣) David Steindl-Rast describes as

“that kind of happiness that doesn’t depend on what happens.”

It is vital, of course, to stay in touch with the world. But it is only by

having some distance from the world that you can see it whole, and understand

what you should be doing with it.

For more than 20 years, therefore, I have been going several times a year—

often for no longer than three days—to a Benedictine

hermitage

(修道院),40

minutes down the road, as it happens, from the Post Ranch Inn. I don’t attend

services when I am there, and I have never meditated, there or anywhere; I just

take walks and read and lose myself in the stillness, recalling that it is only

by stepping briefly away from my wife and bosses and friends that I will have

anything useful to bring to them. The last time I was in the hermitage, three

months ago, I happened to meet with a youngish-looking man with a 3-year-old

boy around his shoulders.

“You’re Pico, aren’t you?” the man said, and introduced himself as

Larry; we had met, I gathered, 19 years before, when he had been living in the

hermitage as an assistant to one of the monks.

“What are you doing now?” I asked.

We smiled. No words were necessary.

相关推荐

-

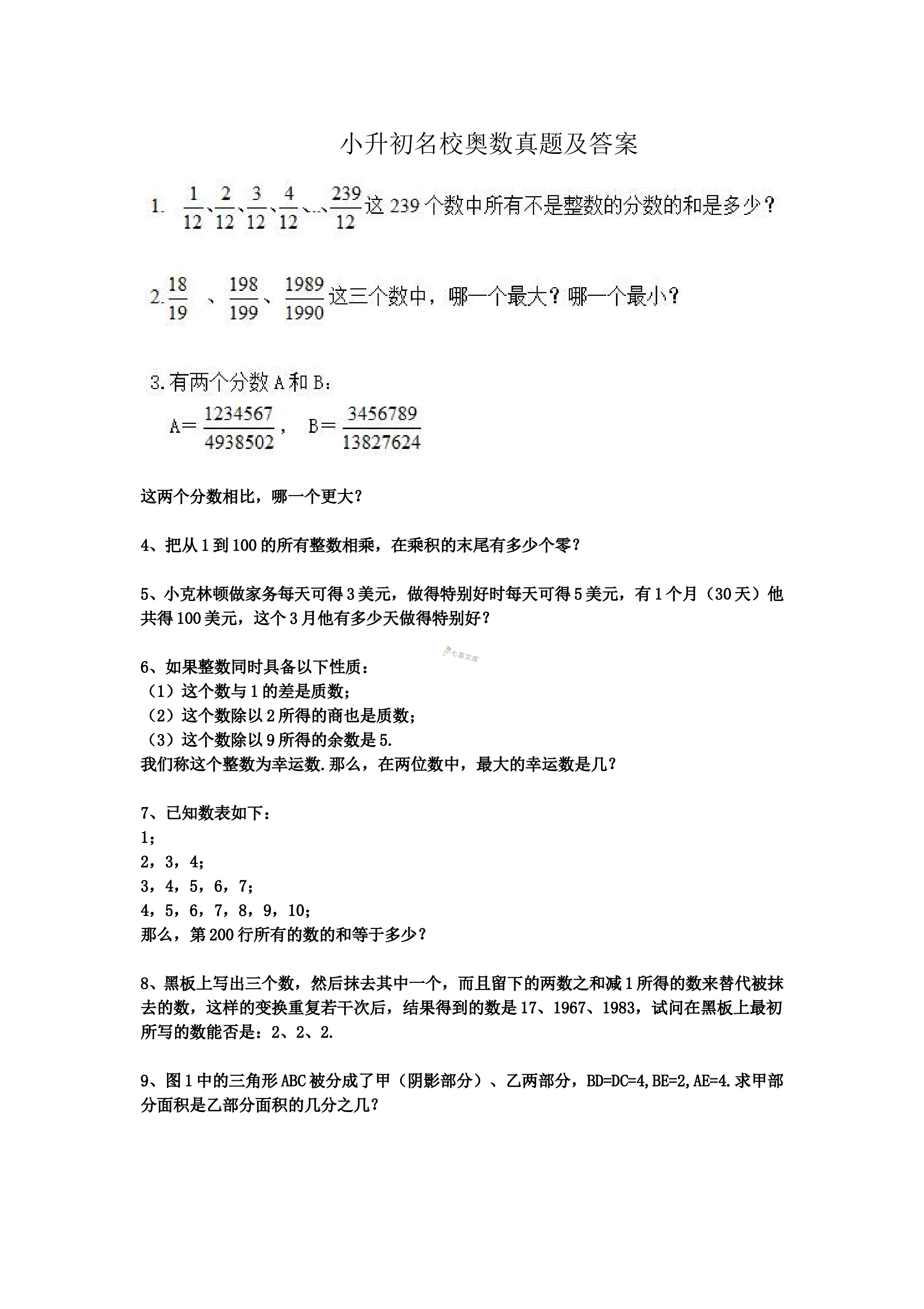

小升初名校奥数真题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-09 41

2024-11-09 41 -

2023-2024学年七年级下册数学第一章第七节试卷及答案北师大版VIP免费

2024-11-09 84

2024-11-09 84 -

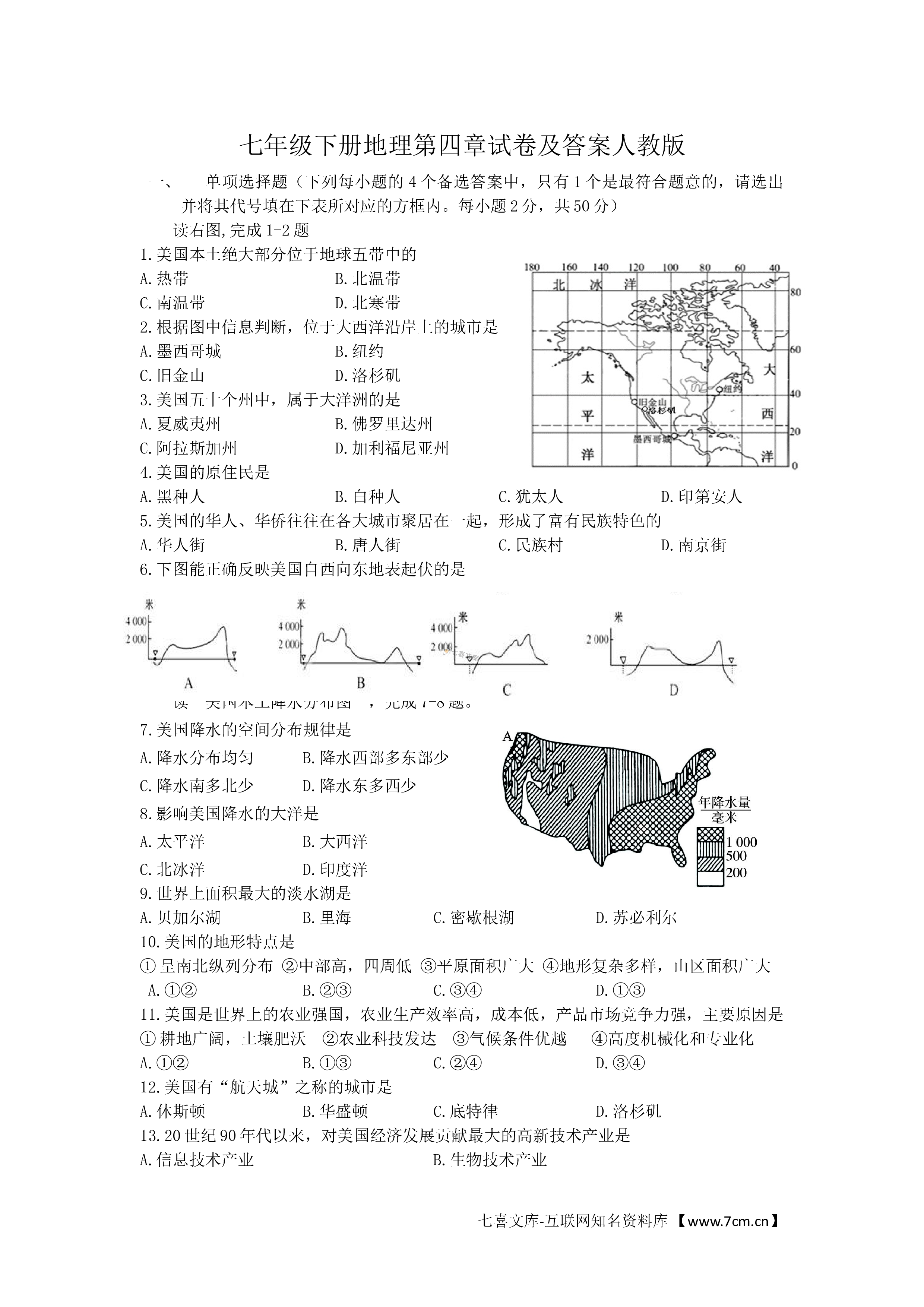

七年级下册地理第四章试卷及答案人教版VIP免费

2024-11-10 51

2024-11-10 51 -

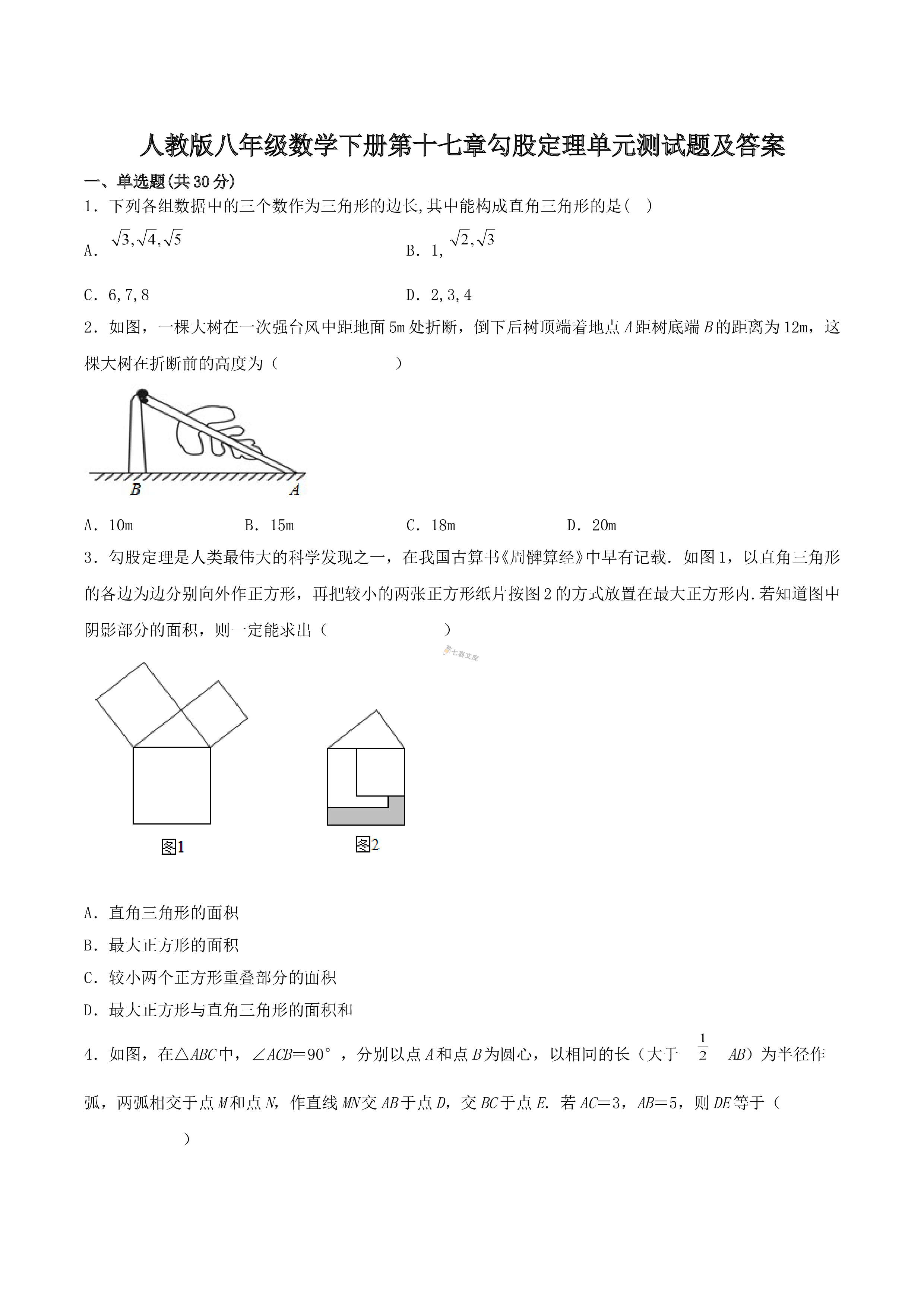

人教版八年级数学下册第十七章勾股定理单元测试题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-10 427

2024-11-10 427 -

2011年成人高考专升本生态学基础考试真题及答案VIP免费

2024-11-12 43

2024-11-12 43 -

2023年武汉工程大学教育管理学考研真题VIP免费

2024-11-14 17

2024-11-14 17 -

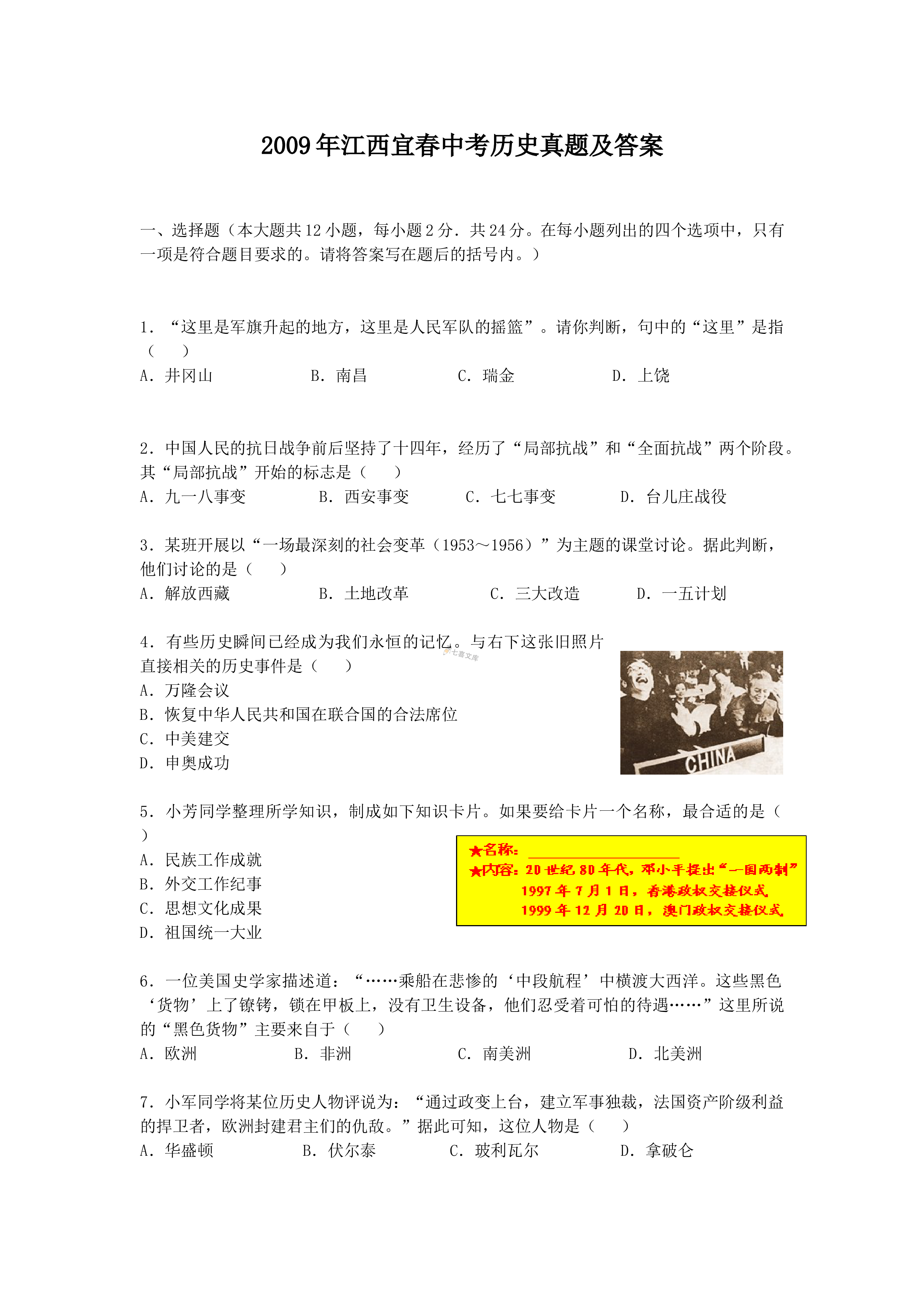

2009年江西宜春中考历史真题及答案

2024-12-24 8

2024-12-24 8 -

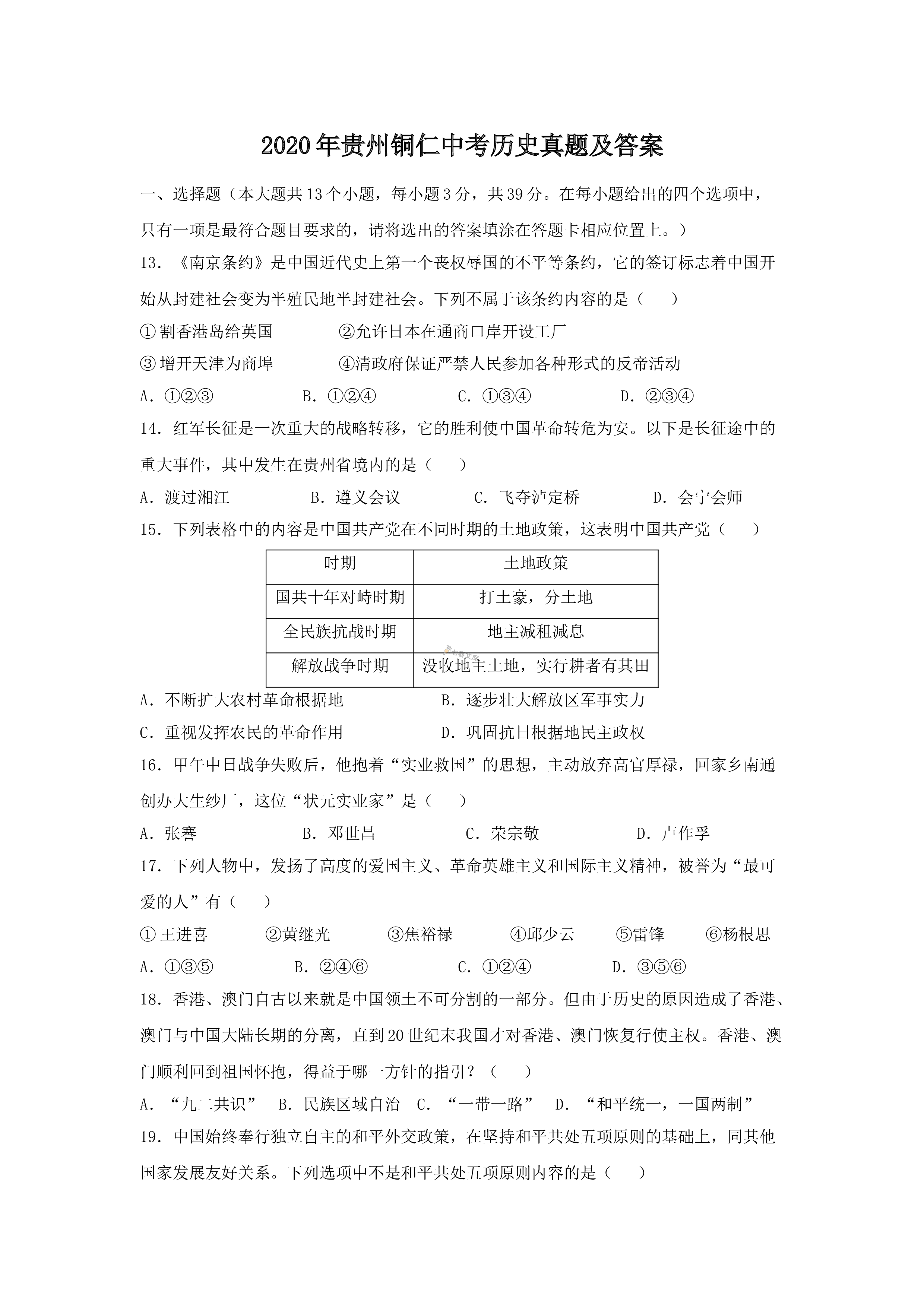

2020年贵州铜仁中考历史真题及答案

2025-01-04 5

2025-01-04 5 -

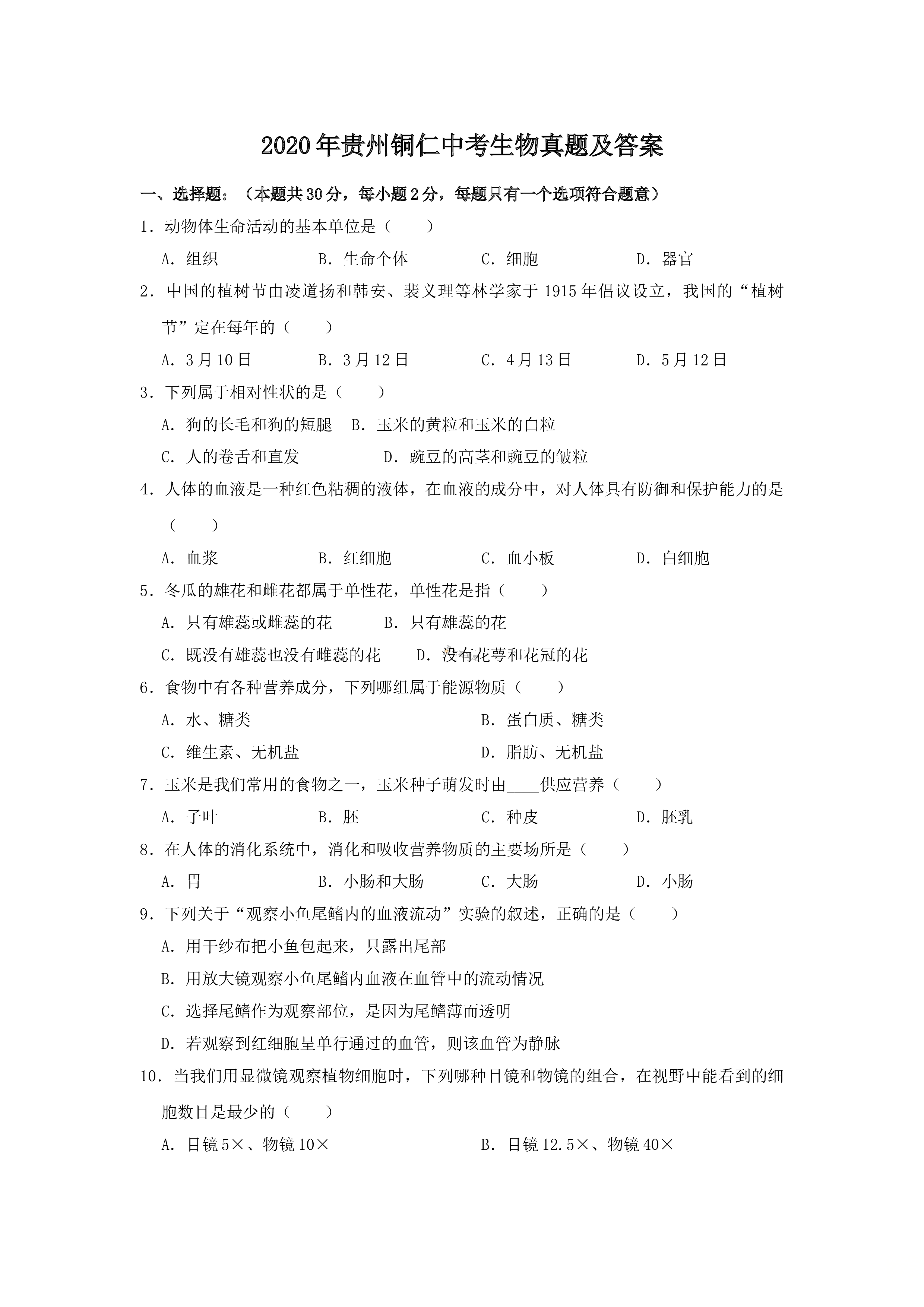

2020年贵州铜仁中考生物真题及答案

2025-01-04 6

2025-01-04 6 -

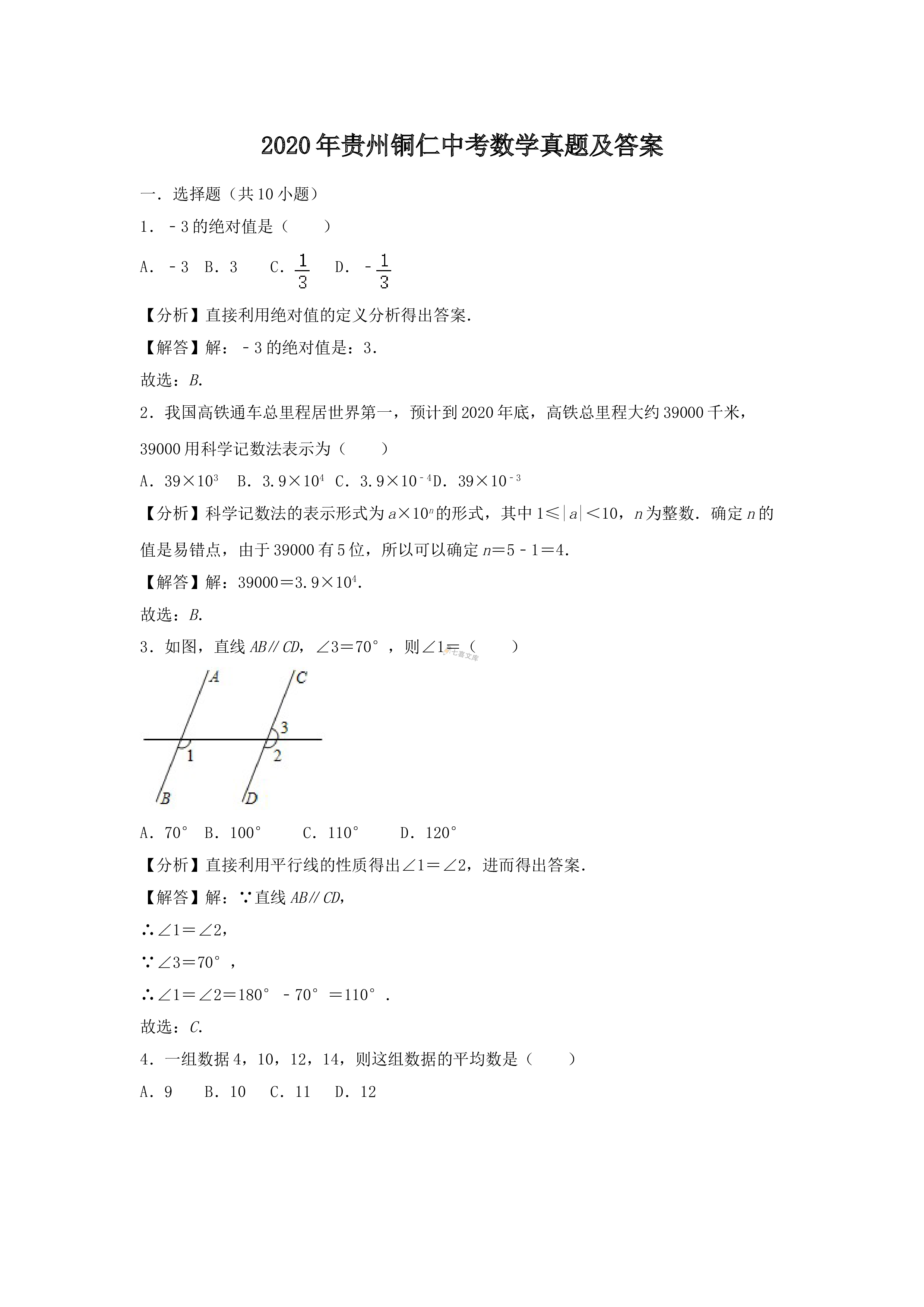

2020年贵州铜仁中考数学真题及答案

2025-01-04 8

2025-01-04 8

分类:行业题库

价格:3.2金币

属性:33 页

大小:134.5KB

格式:DOC

时间:2024-11-14

相关内容

-

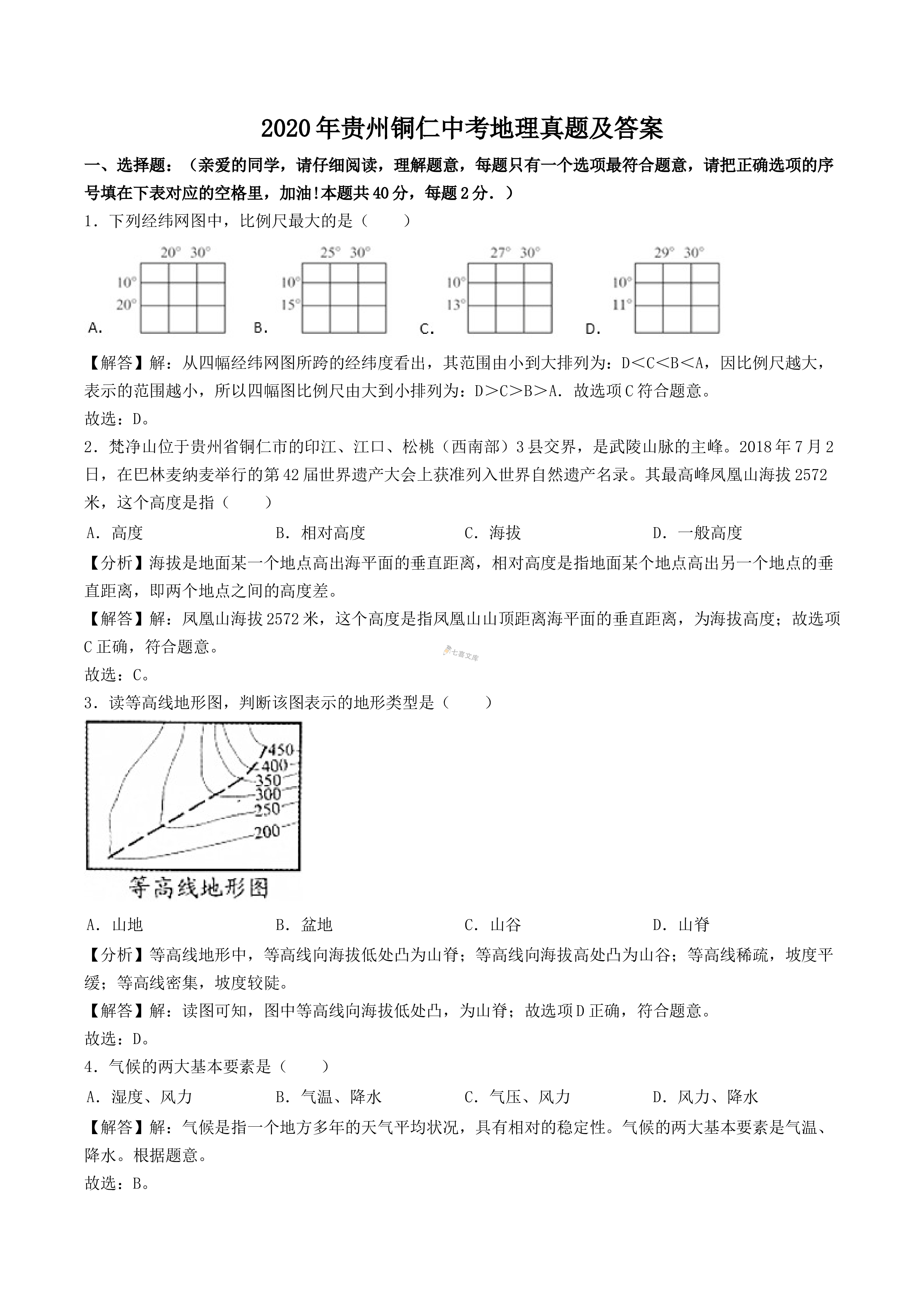

2020年贵州铜仁中考地理真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

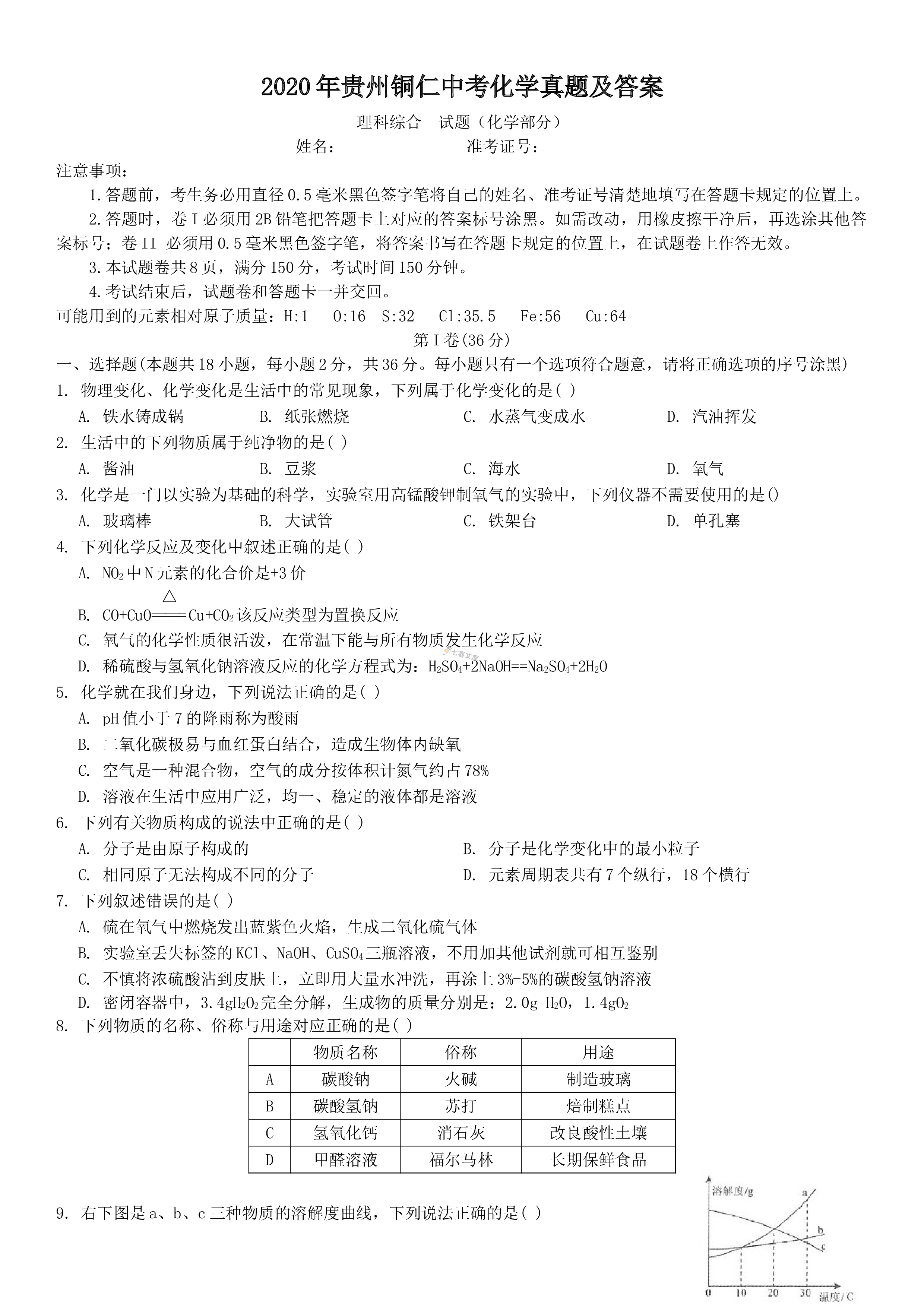

2020年贵州铜仁中考化学真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

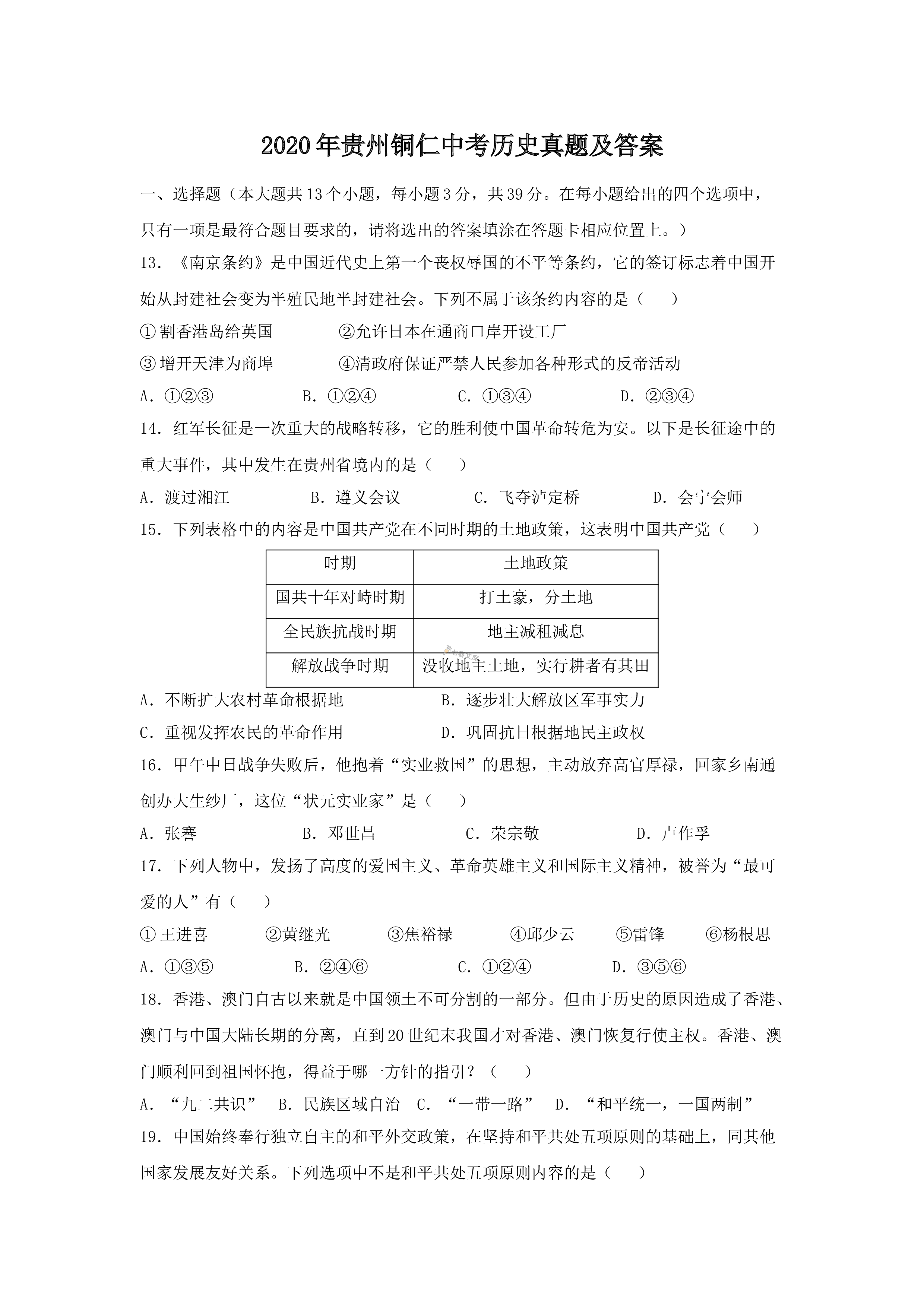

2020年贵州铜仁中考历史真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

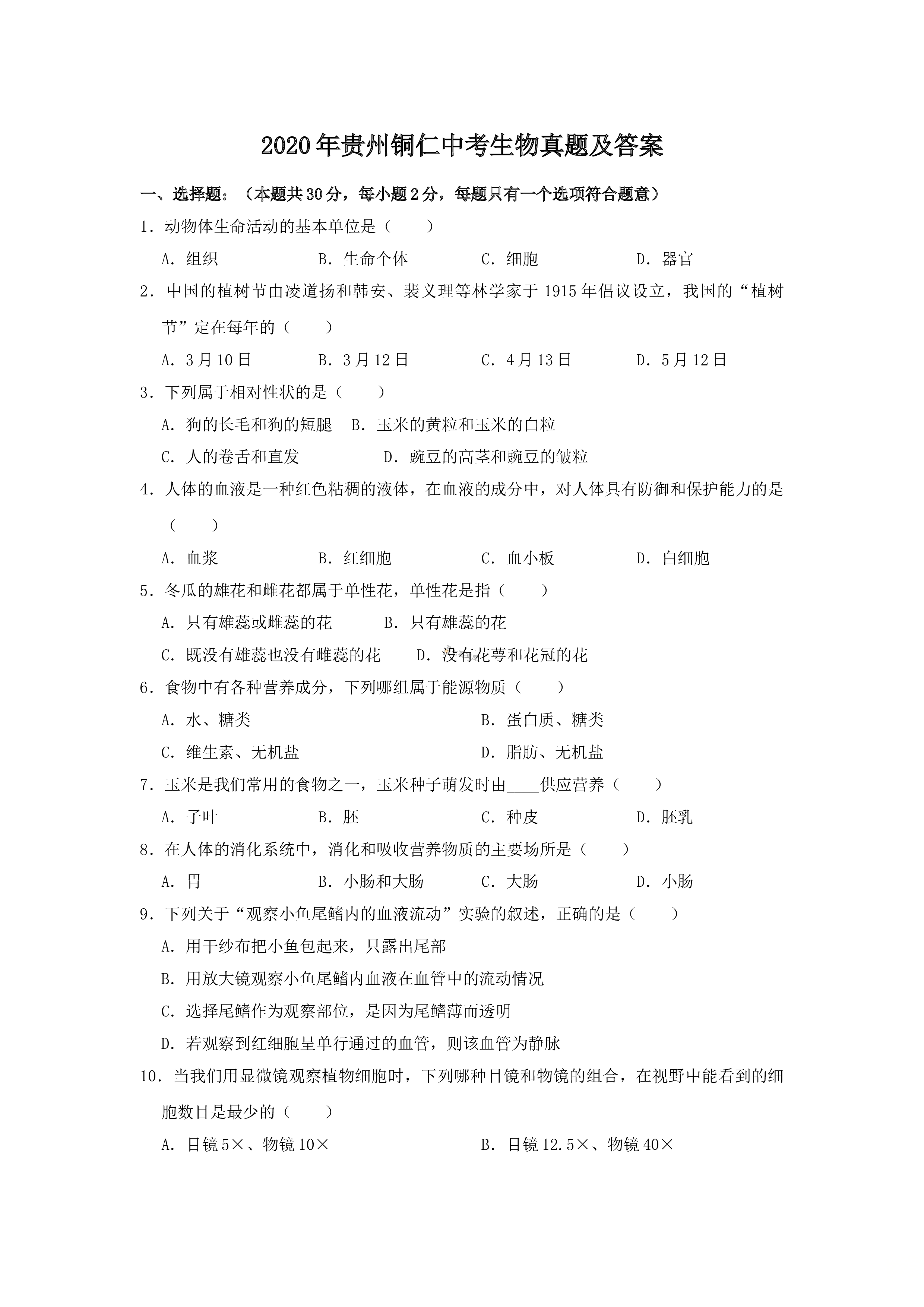

2020年贵州铜仁中考生物真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币

-

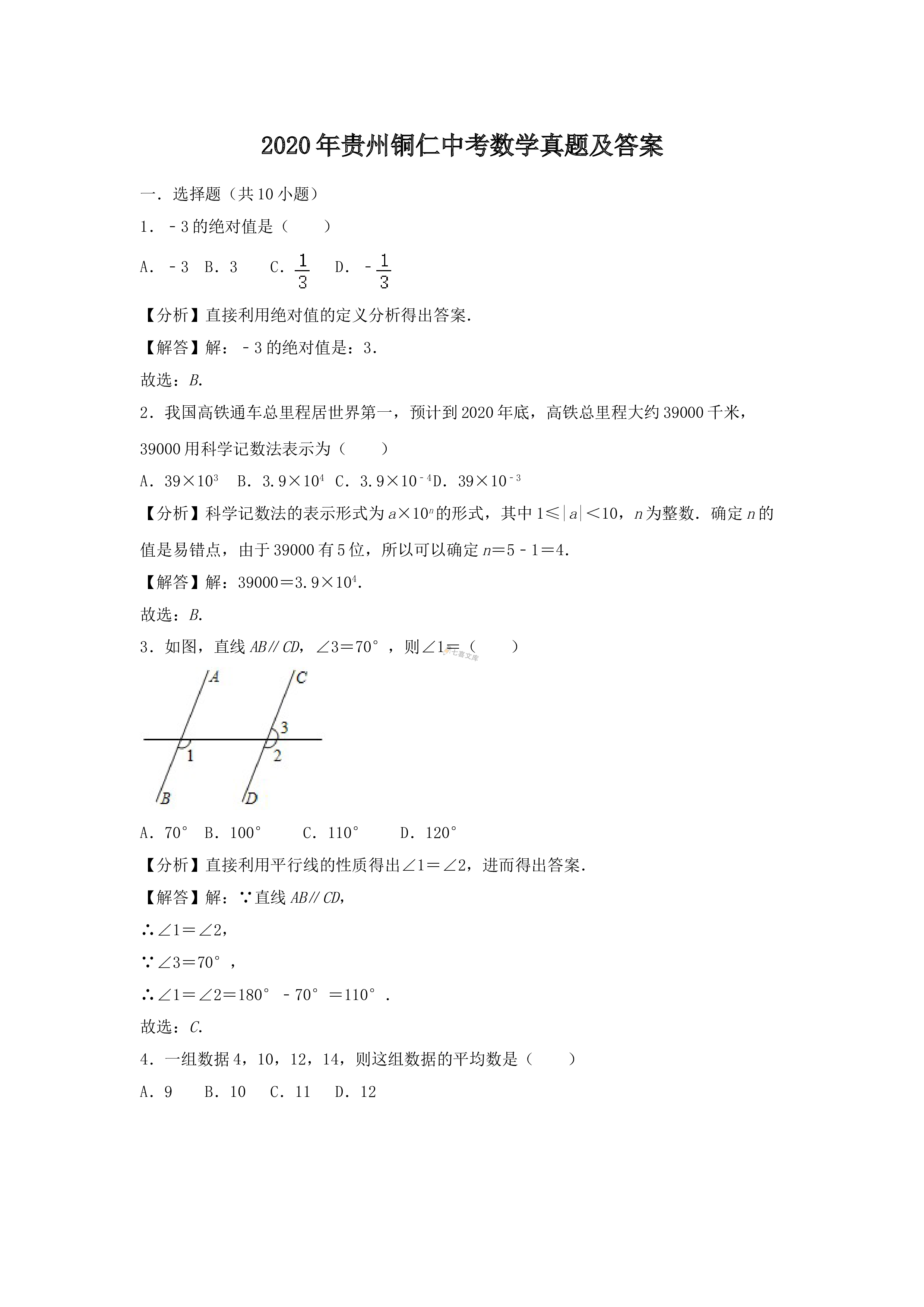

2020年贵州铜仁中考数学真题及答案

分类:行业题库

时间:2025-01-04

标签:无

格式:DOC

价格:3.3 金币